Pricing has always been a tricky topic. On the one hand, you want to attract as many customers as possible, but you also want to avoid leaving money on the table.

There are numerous product pricing tactics, such as competitive pricing, cost-plus pricing, and price skimming. But do they actually work?

Do customers really care that much about how expensive it is to you to maintain the product or how much other competitors charge?

Spoiler alert: no, they don’t.

Table of contents

What is willingness to pay (WTP)?

The most crucial factor that impacts the chance of sales is the customer’s willingness to pay.

In short, willingness to pay — often abbreviated as WTP — is the maximum price a customer is willing to pay for a given product or service. It comes from the value the customer perceives they receive.

It’s usually a dollar figure, but for groups of customers, it might be represented as a range, such as $10–15 per month.

Since customers care more about the value [they believe] they get, using willingness to pay as a guiding light is more reliable than just adding margins on top of the cost or undercutting competitors.

How to test willingness to pay

It all sounds great in theory, but how do you actually discover how much your potential customers are willing to pay?

You can’t just ask “how much would you pay for X?” The answers would be too biased to be useful anyhow. Besides, it’s not your customers’ job to price the product effectively — they’ll always aim for a bargain.

However, there are a few techniques you can use to get a better understanding of your customers’ WTP. While no single one is perfect, if complemented by each other and other research, these should give you a good picture of customers’ willingness to pay.

Price-points

The first technique is probably the most straightforward one, but it’s also a good starting point to anchor your exploration.

Show customers your product/prototype and ask customers three questions. What price do they find:

- Cheap?

- Expensive?

- Outrageous?

As a rule of thumb, cheap means it’s a bargain, expensive is closest to their actual willingness to pay, and outrageous means it’s too much for them to pay.

Van Westendorp’s Price Sensitivity Meter

The Van Westendorp’s Price Sensitivity Meter is a more complex and robust version of price-point, often used by the most well-known consulting agencies.

To use this model effectively, you need a big sample of data — closer to hundreds of respondents, not tens.

This time you ask four questions. What price do they find:

- Too cheap?

- Not expensive?

- Not a bargain?

- Too expensive?

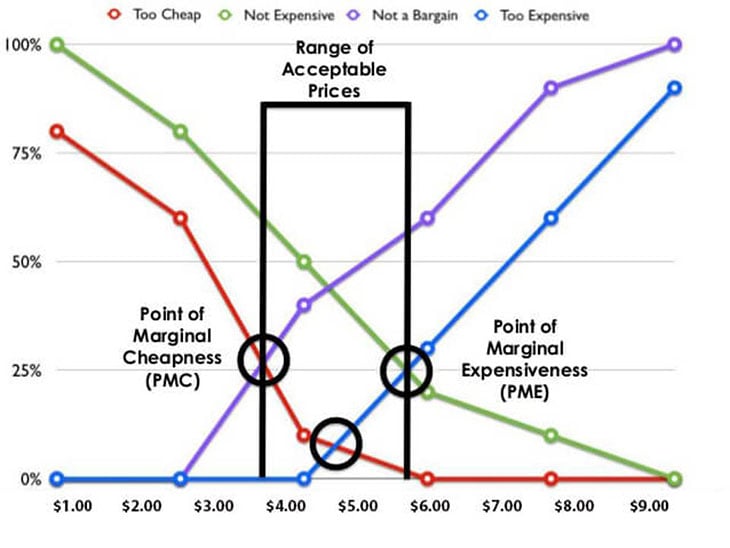

Then, you visualize the data using a cumulative frequencies diagram:

The diagram will help you identify three crucial price points.

- Point of Marginal Cheapness (PMC): where “too cheap” and “not a bargain” cross and should be the minimum price you charge

- Point of Marginal Expensiveness (PMC): where “not expensive” and “too expensive” crosses should be the maximum price you charge

- Optimal Price Point: where “too cheap” and “too expensive” cross and is hypothetically the most optimal price to charge

The range of the point of marginal cheapness and the point of marginal expensiveness is a scale of acceptable prices for your customers. Go beyond that and you start losing customers; go below that and you are leaving money on the table.

Indexing

Indexing is a good technique to compare yourself with competitive and alternative products. Choose a competitor and ask your customer to index your product compared to the competitor.

Say you are building an alternative to Jira. Ask a prospective customer two questions:

- If Jira indexed at 100 points in terms of value, how would you rate our product?

- If Jira indexed at 100 points in terms of price, how much would you pay for our product?

It helps you compare how customers perceive you compared to other products, plus it might lead to additional discoveries.

If customers rate you better than Jira (say, 120 points) but are willing to pay less (say, 70 points), why is this so? Ask follow up questions if needed.

Direct questions

Although you shouldn’t ask customers how much they are willing to pay for a product or service, you can ask them directly if they are willing to pay a specific price.

It’s a good validation exercise if you already have some well-researched numbers in mind.

You could ask them if they are willing to pay $30/month for a subscription and wait for the answer. If they say yes, ask them if they are willing to pay $35/month and keep increasing the price until they say no. Then evaluate at which price point the majority of the customers stopped.

Probability questions

Probability questions are another great validator once you have something in mind. Similarly to direct questions, give your customers a specific price, but this time ask them how likely they would be to purchase the product for that price on a scale of 1–5.

1–3 means the price is too high for them.

4–5 means they are prospective buyers.

As a rule of thumb, if a customer says 5 out of 5, there’s roughly a 50 percent chance they’d actually purchase the product.

“Build your own”

The techniques mentioned above can also be used for specific features, not only whole products. Doing so allows you to test various combinations of features/options.

An interesting tool is the “build your own” exercise. List out all potential/existing features with a respective price tag (based on their WTP) and ask potential customers to choose features they are most interested in. Needless to say, the more features they choose, the more expensive the product becomes.

It’s not only another way to understand how much they are willing to pay (at what price point do they stop?) but also tells you what product capabilities are most important to them.

Mock sales/actual sales

An ultimate willingness to pay the validator is an actual sale.

If you have already built the product — hopefully optimizing for previously researched WTP and focusing on features customers are most willing to pay for — then try to sell it. Focus more on CVR and LTV than actual numbers. The latter depends on multiple other factors, such as your growth strategy.

If you don’t have it yet, then try to sell the prototype to customers as if it was an actual product, and once they agree, just tell them it’s not ready yet, and you can add them to the waitlist.

Conclusion

Willingness to pay (WTP) is a key factor you should consider when setting a price point. It comes from customers’ perceived product value, which is a significantly more important factor than your costs.

There are numerous tactics to test for willingness to pay. These include:

- Price points

- Van Westendorp’s Pricing Model

- Indexing

- Direct questions

- Probability questions

- “Build your own” exercise

- Mock sales/actual sales

While none of these exercises will give you a definitive answer on how much you should charge, combining them together with various pricing experiments will help you find the most optimal price point for your product.

Featured image source: IconScout

The post What is willingness to pay (WTP) and how to test it appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

from LogRocket Blog https://ift.tt/OoZ0NnY

Gain $200 in a week

via Read more